For many young working-class Filipinos, snagging a job on a cruise ship has become the brass ring on its own. It promises not only substantial monetary rewards but also the formerly unattainable luxury of seeing the world. It means better opportunities, too, for people back home—quality education for the kids, health care for the whole family, basically a brighter future for everyone.

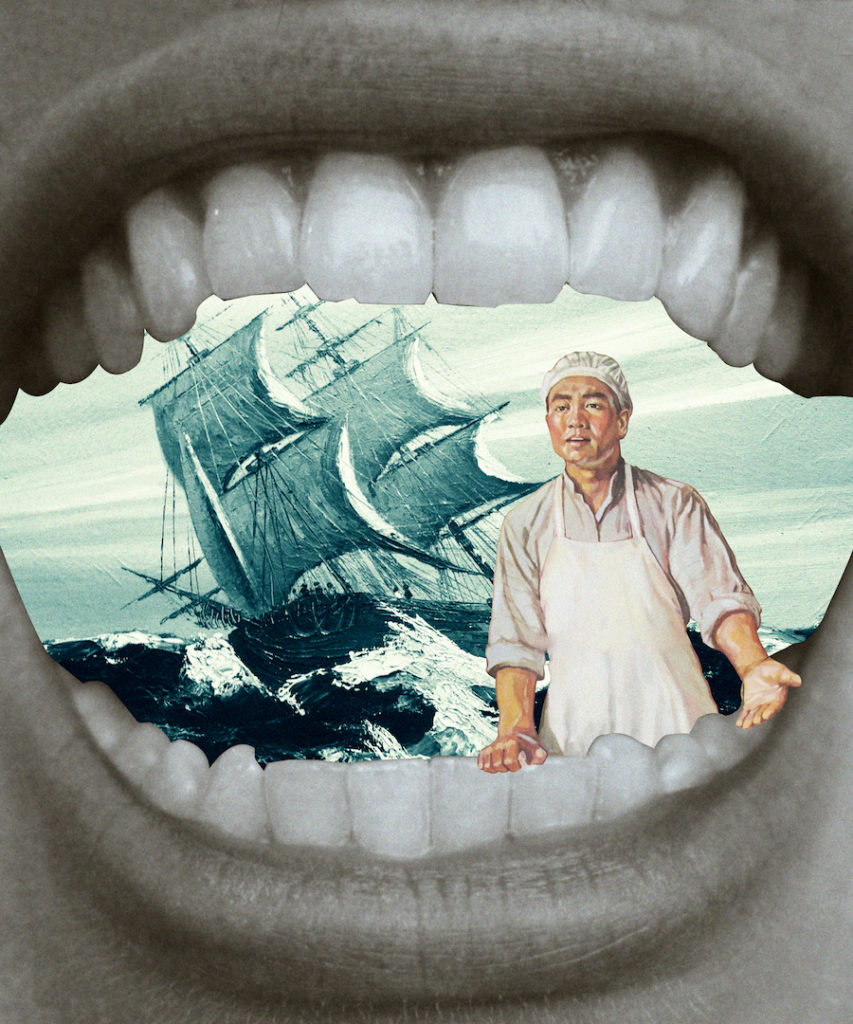

However, life at sea is not for everybody. You literally need a strong stomach for it. Seasickness is obviously an issue and you cannot work under nauseating conditions. But, other than that, these former Filipino cruise ship workers speak about the other numerous challenges they faced which, despite the good money and nomadic lifestyle, turned their “Love Boat” fantasies into a living nightmare.

The rat race

Jonas Banaag, 24, and Jave Tabligan, 27, are servers at Cibo. They have both tried working on cruise ships but decided to come home and continue working at the front of the house but on land. Tabligan did not finish his contract and only lasted three months at sea. “Nahirapan ako sa supervisor ko,” he admits.

Banaag, the breadwinner of his family, stuck it out for two years. However, he too shares stories of difficult encounters with their foreign bosses. “’Pag pinapahirapan kami sa barko, tawag namin doon ‘hard times,’” he says. Something that Filipino workers seem to experience more than others.

They point out that Filipino workers are often assigned menial jobs regardless of their work experience on land. Banaag is an experienced bartender. He was surprised when he was tasked with washing glasses and preparing garnishes. “Pero ’yung mga European, kahit bago, bartender agad ’yung position,” he says. “Ang nakakatawa, kailangan pa namin turuan minsan.”

An impenetrable glass ceiling

Both Banaag and Tabligan talk about the good camaraderie among the crew onboard, but it was mostly within their own cliques. “Siyempre ’yung mga kanya-kanyang lahi,” Banaag says, “nagsasaluhan kapag may mali. Nagdadamayan.”

“‘Pag may ginawa akong tama, balewala sa kanya. Pero pag kasamahan ko na Indian gumawa, ‘good job’ daw,” says Jave Tabligan.

However, they claim this might also explain why it was so difficult for Filipinos to get ahead. They confess that most of the bosses on the ships they have worked on were European and that it was very rare to find a Filipino supervisor onboard. The Filipino workers were often tied in 10-month contracts; the Europeans’ work contracts were shorter and ran for three to six months. Tabligan explains that by the time they proved their mettle, their supervisor’s tenure would expire and a new boss would take over. “Panibagong pasikat na naman,” he sighs. And sadly, the supervisors were almost never Filipino and chose to promote from within their own groups.

Banaag speaks of a former supervisor who made him “time out” to record the end of his shift, then forced him to keep working anyway. “Meron kasi kaming rest hours na dapat matupad, kung hindi masisita sila ng POEA,” Tabligan explains. However, there are some people who chose to make them work overtime without pay.

Tabligan’s supervisor, the primary reason he left before his contract even lapsed, really broke his spirit. “She would really pick on me,” he recalls. “’Pag may ginawa akong tama, balewala sa kanya. Pero pag kasamahan ko na Indian gumawa, ‘good job’ daw.”

The sea, it keeps calling me

For now, both guys are happily working at a restaurant where pay is competitive and the benefits are good. Despite the trauma of a horrible boss, Tabligan is hoping to work on another cruise liner again. He’s crossing his fingers that, when that happens, he will not go through “hard times” with his supervisor.

Banaag, though, is planning to stay put for now. “Nakaka-homesick talaga,” he admits. However, he has plans of starting a family soon since marriage is on the horizon. He knows that he will have to make sacrifices again to support his brood. “Ayoko na ng cruise ship,” he confesses.

Both men recall the expenses onboard, since basic commodities such as toiletries and snacks were not covered by their work packages. They were paid in US dollars, yet the currency on board was the euro. The staff usually waited until they docked before they did their personal shopping, otherwise making purchases aboard the ship could get expensive.

Banaag says that if he must go back to sea, it will be working on a cargo ship as a cook in the mess hall. “Wala masyadong gastos,” he claims. “Tapos wala ka masyadong pakikisamahan, ’yung crew lang talaga ng barko.”

While both men claim that working on a ship is “five times harder” with all the politics and complications, the pay is just too good to ignore. Until local wages improve, Filipino men and women will continue to look out towards uncertain waters hoping for better opportunities.

Originally published in F&B Report Vol. 15 No. 4

That’s only some of the realities happened and still happening until now..you need to swallow all of the things going onboard the ship or else you end up not to finish the contract.