The entrance is unassuming: a tasteful, if understated, white facade dots the San Jose Airport Road, a vibrant strip by the fringe of Tacloban City’s downtown area and a mere seven-minute drive to the airport. Flanking the structure is a sleek black sign that reads Rovinare by Jose Karlo’s Coffee, a marker that is nearly easy to miss.

Enter its doors, however, and the interiors tell a much richer story. Rovinare is fully decked out in weathered metal and wood, and one can’t help but be drawn to a massive teal hunk of metal—a 3,000-kilogram press machine, once used to shape ice from raw blocks—that sits in the middle.

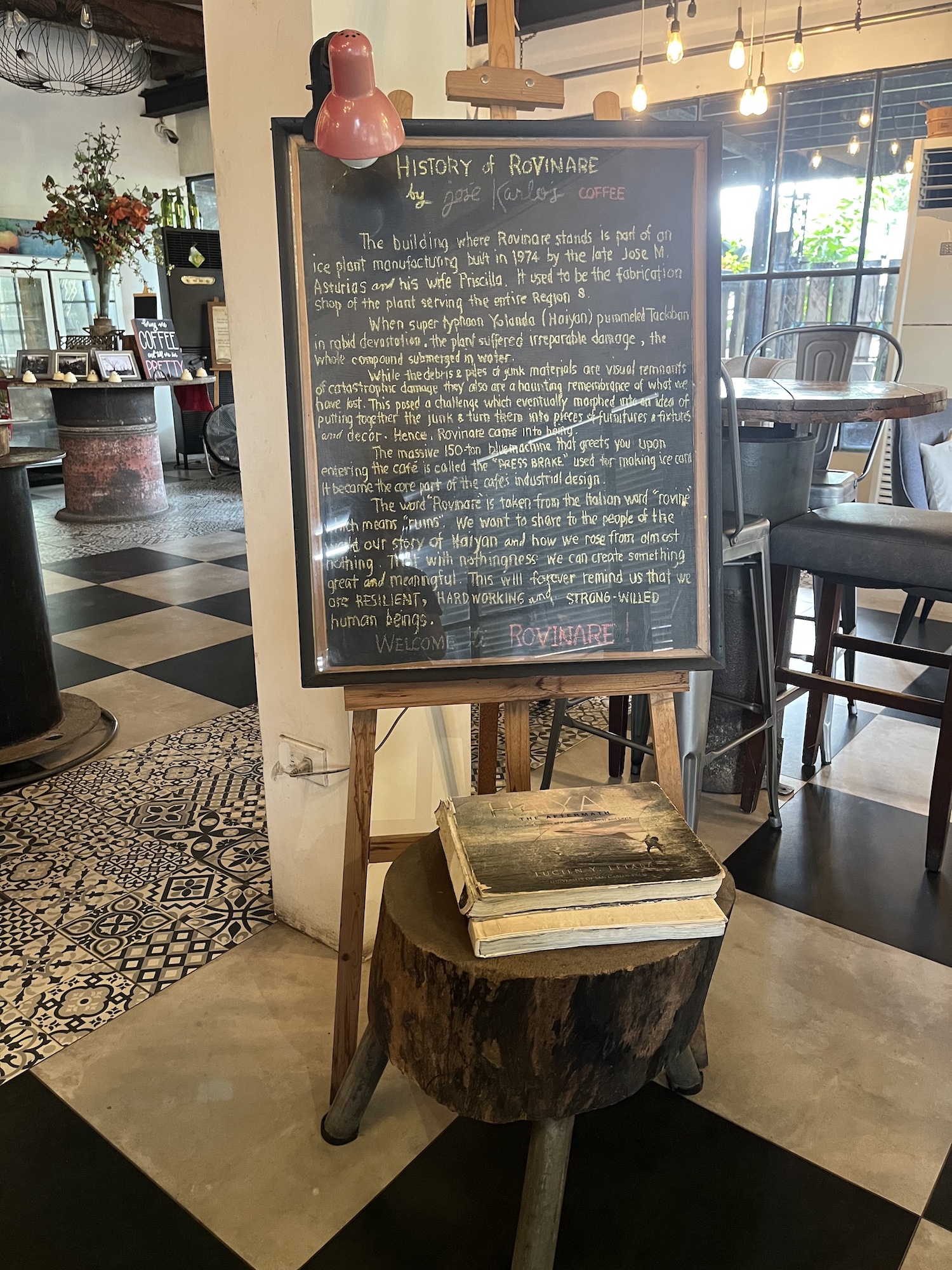

A signboard greets guests by the foyer, capturing the cafe’s history in a nutshell: Rovinare stands on part of an ice plant, taking place in its former fabrication shop after the entire compound—and its machines—were submerged in water when typhoon Yolanda (international name Haiyan) ravaged the city in 2013.

Rovinare: Remnants of its past

Named after the Italian word rovine or ruins, Rovinare is a beautiful yet haunting reminder of its history. The patina and deep tones from its metal and wooden furnishings are all repurposed from the ice plant’s old equipment and materials that had been heavily damaged in the storm—remembered as one of the world’s most destructive natural disasters in recent memory.

They have since been lovingly repurposed and rebuilt into details that lend the cafe’s character: The plant’s many ice cans now make up Rovinare’s counter surface as well as its window panels and shelves; chandeliers fashioned from the factory’s cooling fans in its compressors; pipes for table stands; a “mushroom table” filled with nozzles taken from the plant’s water filtration system now serves as a memorabilia shrine of sorts. There are other details that reveal themselves the longer you linger, too.

Rovinare is owned by Arlene Asturias, the proprietor of Jose Karlo’s Coffee (affectionately called JK by its regulars)—a 22-year-old establishment and a pioneer of Tacloban’s café scene at the heart of the city center. Her husband ran the ice plant within the compound, a multi-generational family business.

Locals may recognize many of its items on the menu as beloved classics from the original JK café, with whom it shares its culinary DNA, but there are other exclusives, too: from Italian influences such as the chicken tosca with pasta (their version of chicken piccata) and tomato basil risotto with crusted fish to beverages that flaunt their local roots, such as the Mescoccino Roscas, an ice blended coffee featuring the famous Tacloban cookie.

“Rovinare is a story of resilience,” Arlene Asturias shares. “We lost all of our businesses, everything. That’s why I [wrote] that phrase, ‘We were left with almost nothing,’ but [from nothingness], we were able to [rise up]… [we] can make it into something beautiful and meaningful.”

“Rovinare is a story of resilience,” Asturias shares. “We lost all of our businesses, everything. That’s why I [wrote] that phrase, ‘We were left with almost nothing,’ but [from nothingness], we were able to [rise up]… [we] can make it into something beautiful and meaningful.”

To the side of the café counter is a wall that serves as a reminder of the city once dubbed Yolanda’s ground zero: multiple photographs of the ruin that once befell Tacloban visually capture the extent of the typhoon’s damage.

Yolanda and their story of survival

Like other residents of Tacloban, the memory of Yolanda hits home for Asturias, who was with her younger children in the compound when the storm made landfall on Nov. 8, 2013.

She remembers going to their home’s basement with her eldest son to see whether the water had begun seeping through. Just minutes after they had gone back up, the light bulbs on their ceiling had burst, and the flood had already reached the first floor.

Fallen trees had obstructed their home’s back door, so the family made their escape through the front door, where the ice plant, situated on lower ground, had been submerged up to the roof.

The wind howled like a choir, Asturias recounts. She instructed her 17-year-old to swim to the top of a nearby truck to escape the rising water levels as her younger children, aged 10 and 5, clung to her for dear life.

“I remember saying, ‘I was ready to go, just spare my children,’” she narrates. Then, the floods stopped rising.

“Our workers and their families came in and took shelter in [some of the] buildings at the ice plant, so we were taking care of each other. We were sleeping in one bed [as] we had no doors or windows, and the house was full of mud,” she says.

With no water available in the first five days of the typhoon’s wake, the family got by with the soft drinks that were being distributed by a nearby bottling plant. As soon as the first mercy flights became available, Asturias and her husband made sure to send their children to Manila while the couple stayed behind.

“When [my children] left, parang nanghina ako. My husband and I began to talk about what was next for us, we didn’t know what to do. I stayed in one corner, thinking of what was going to happen to us. After hours, I stood up and said, ‘I’m not going to let this one put me down. I need to survive this.’”

“When [my children] left, parang nanghina ako. My husband and I began to talk about what was next for us, we didn’t know what to do. I stayed in one corner, thinking of what was going to happen to us. After hours, I stood up and said, ‘I’m not going to let this one put me down. I need to survive this.’”

Asturias and her husband soon moved close to JK Coffee in the city. “JK was also destroyed, but roof lang ng third floor ’yung nawala. The ground floor was filled with mud, but it could be easily fixed. When I visited the café, I said, I think I can do something. Maybe I can run it.”

The following week, she asked her husband if she could fly to Manila to look for signs that she should start operating the café again. She would try to have the espresso machine fixed and call all her suppliers in a bid to convince them to provide stocks with flexible terms.

“I will never forget that day. We did not sleep just to fix the place up again kahit wala siyang window panels—broken pa ’yung windows. Noong maayos ’yung coffee machine, sabi ko, just give me two days I’m going to open this. So we rearranged the place, we washed down the sofas and chairs,” she says.

“Lahat ng suppliers were very supportive. Pag-uwi ko, dala ko ‘yung technician ng coffee machine,” she says. By December, portions of the city had power back, including Jose Karlo’s Coffee. She resolved to open on the 11th, serving only one item—hot coffee.

“I will never forget that day. We did not sleep just to fix the place up again kahit wala siyang window panels—broken pa ’yung windows. Noong maayos ’yung coffee machine, sabi ko, just give me two days I’m going to open this. So we rearranged the place, we washed down the sofas and chairs,” she says.

“One and a half days later, I said, ‘I’m going to open it.’” Jose Karlo’s doors reopened with a single-item menu—to the city’s delight. “I had this long line waiting for coffee, especially the foreigners. When they saw that my technician was fixing the machine by the window where he can get enough light, kasi ang dilim dilim noon, kung may dumadaan, they’d say, ‘Oh wow! Are you going to open soon?’ So when we opened, talagang we had pila. That was really something.”

A day after the blockbuster turnout, she thought that maybe they could start selling iced coffee, too. “We were looking for ice and yet we ran an ice plant. Before Yolanda, we were selling our ice for only P210 per block at the time. When we went around, we saw these big trailers that were selling ice—I think they were coming from Davao and they traveled all the way here just to sell ice—and we were buying it for P1,200 for one block.”

On the fourth day, she thought they could slowly expand the menu again. “Maybe we could start selling sandwiches, kahit isa lang. I bought eggs so I could make an egg sandwich. Alam mo ’yung egg magkano? P20 per piece. That’s how expensive it was.”

“We [make] our own bread, but we didn’t have a source [of] raw ingredients. I asked my husband if he had contacts in Samar, maybe we could purchase flour there. And we did. First, a sack of flour was delivered to us, then I was able to make bread. So we were able to start serving a few sandwiches.”

“We [make] our own bread, but we didn’t have a source [of] raw ingredients. I asked my husband if he had contacts in Samar, maybe we could purchase flour there. And we did. First, a sack of flour was delivered to us, then I was able to make bread. So we were able to start serving a few sandwiches.”

Asturias took it one day at a time with Jose Karlo’s Coffee, slowly acquiring equipment and procuring stocks from Manila that would be deployed through trucks. “We would contact a trucking service, and it would be delivered to me in three to four days. Talagang nag-s-stock lang ako. Everything was coming from Manila, and bi-byahe ’yung truck all the way [to Tacloban]. Since my sister was in Manila, she was helping me with everything I needed. I-shi-ship out niya, then when the truck arrives, I would reorder immediately para continuous lang ’yung flow.”

Within a month, the café returned to full operations. Despite being roof-less, Asturias managed to cover up with a tent on the café’s third floor, which had a function room, and began accepting reservations mostly from non-government organizations providing humanitarian aid around the region. “We were the first café that opened at the time, and the third [F&B establishment] that opened [in the city after Yolanda],” Asturais shares. The income streams allowed the café to slowly gain back what had been lost and set the stage to continuously rebuild.

Beginning again

“The whole San Jose [area] was a quiet place. Walang kahit na ano dito,” Asturias shares of Rovinare’s history. Yet since Rovinare opened its doors in 2016, the area has transformed into a thriving district teeming with establishments—a testament to the city’s strength of character.

Built in the aftermath of Yolanda, Rovinare was conceived literally amid the rubble. Asturias finally returned home to the family compound in March 2015, over a year after the typhoon’s devastation. The place was trashed, filled with rusting debris and damaged components. Yet the long-time café owner saw an opportunity to rebuild from its scraps and remnants.

The plant’s fabrication shop faced the San Jose Airport road, filled with machines her husband deemed beyond repair. Asturias wanted to take advantage of the property’s proximity to the airport, which was mere minutes away—an attractive prospect for travelers in transit, especially with nothing else but houses in sight.

“When I went to the shop, I saw it had potential. But of course, I had my hesitations, even when we were about to open. I was just hoping that the market I would get [were] the ones on the way to the airport for their flights. So while waiting, they would have a place to stay and wait for flights na parating delayed,” she narrates.

With the help of her sister, an architect, they began making plans to convert the fabrication shop into a café. They raised the flooring, took three months to take out all the debris and components, save for the press machine, which weighed nearly three tons and was impossible to take out—a facet that Asturias thought made for a rich story.

She also went through the scraps—“like a scavenger,” she laughs—trying to find anything she can make out of. With the help of her daughter, an interior designer, they turned the former ice plant’s rusty components into furniture and fixtures.

Rovinare opened its doors on Nov. 8, 2016, three years after Yolanda’s landfall on Tacloban, which she considers a reminder of the struggles and resilience that she, and many other survivors of the typhoon, exhibited.

To date, Asturias and her family run three cafés across the city, but she holds a special kind of pride for Rovinare. “I built this with blood, sweat, tears, and my heart and love are really seen in that little space.”

To date, Arlene Asturias and her family run three cafés across the city, but she holds a special kind of pride for Rovinare. “I built this with blood, sweat, tears, and my heart and love are really seen in that little space.”

She says rebuilding and gaining back what they had lost took a whole lot of strength, determination, and focus. “Life doesn’t end when you survive a life-threatening situation where thousands of others [have] died and you just pray and thank God for sparing your life. Perhaps at first, you’ll feel you have nowhere to go, but you have a choice. Move forward and allow that experience to be a lesson learned, that being everything you have worked so hard for can be wiped out.”

The entrepreneur also shares that knowing when to ask for help and lean on others is key. “I can’t imagine how I [reopened] so fast. But I was able to do it because of the support of family and friends.”

On the surface of the café’s press machine reads, “We want to share [with] the people of the world our story of Haiyan and how we rose from almost nothing.” Rovinare, in every sense of the word and place, showcases how one can create beauty from ruin.

For more information, check out Rovinare’s Facebook and Instagram