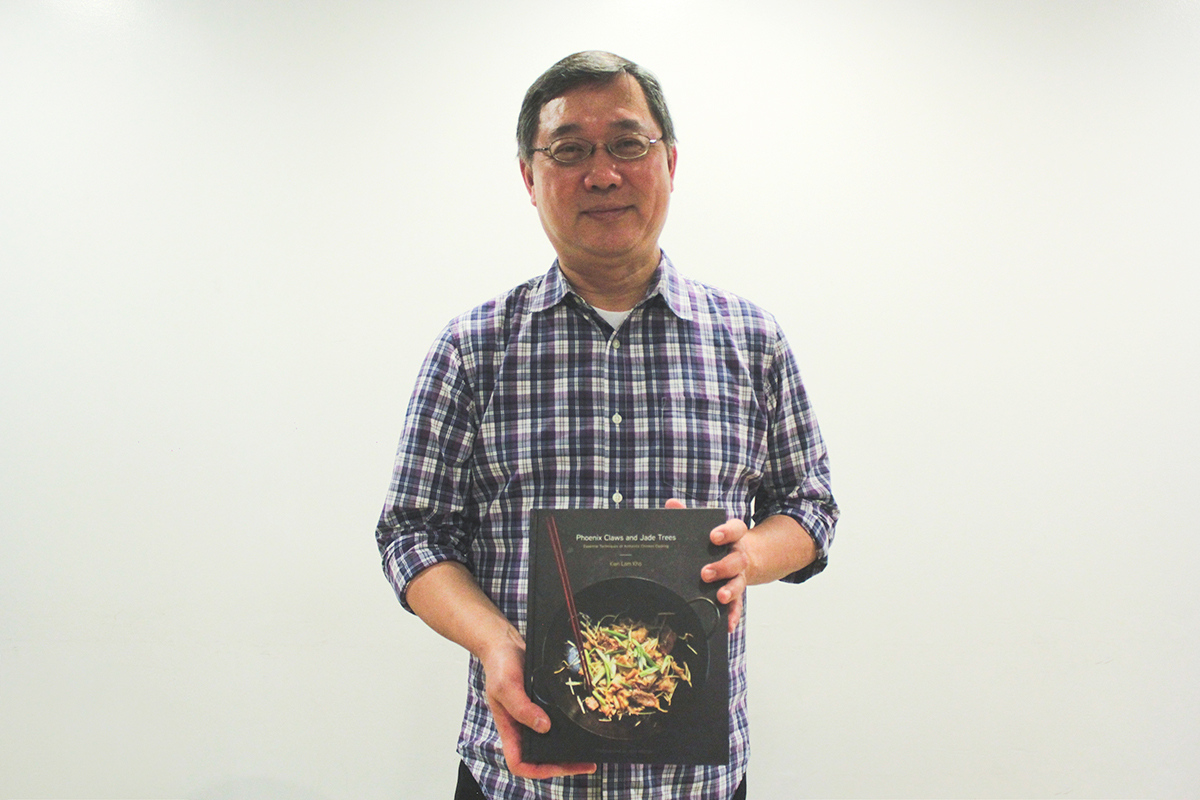

At some point in the process of creating his book “Phoenix Claws and Jade Trees: Essential Techniques of Authentic Chinese Cooking,” Kian Lam Kho encountered several speed bumps, one of which didn’t really come as a surprise. “I had to seek out people who were willing to share their technique because in China they don’t like to share,” he says with a laugh.

Having studied in the US in 1971 and basing himself in New York City since then has only rekindled his deep-seated connection with his roots. “I’m very much like a lot of Asian immigrants in America. You assimilate [into the culture],” he says. “After so many years, I felt like I wanted to rediscover my roots.”

A lot had happened in between including a stint as an aerospace engineer and a software developer, but his work with his 2011 James Beard Award-nominated blog Red Cook and attention-grabbing cookbook that conveys a meaningful honesty with his heritage confirms that he did make the right decision switching careers in his 50s.

What’s the story behind the title?

Chinese cooking has a lot of connection with literature and poetry; poets and scholars are connected to gourmet food. They’re the ones who come up with names. They describe food in very lyrical language and I thought it’s wonderful to present Chinese cooking that way. At the same time it gives this mystery about Chinese cooking and what the book does is demystify it.

Your book is about understanding authenticity in Chinese cooking techniques, but what do you find most challenging about Chinese cuisine?

When I say authentic, I meant that you need to look at the roots of the technique but I’m all for taking what we have in terms of understanding the technique and modernizing it. If you understand this set of techniques then you can do a lot. This may sound chauvinistic but there are a lot of Chinese techniques that have been adapted all over East Asia. If you learn Chinese cooking techniques, you can recreate other Asian food.

Outside China, many chefs were trained by practice rather than by theory so they may not learn the theory of the technique but they know it simply from learning it from a master. I think that’s not enough. One of the problems with that is that you will be able to reproduce the classic dishes over and over again, but if you ask them to be creative and come up with something new and exciting then that’s not going to happen.

“This may sound chauvinistic but there are a lot of Chinese techniques that have been adapted all over East Asia. If you learn Chinese cooking techniques, you can recreate other Asian food,” says Kian Lam Kho.

When you say Asian cuisine, you don’t automatically think of Filipino food. Why do you think that’s the case?

It’s all about exposure. Korean food wasn’t like the way it is now until the last 15, 20 years. Filipino cooking needs a little more exposure and it needs to be modernized. I’m not saying classic Filipino food isn’t good. You should also take advantage of the global availability of ingredients. But there are a lot of flavors in Filipino cooking that I really enjoy. I love dinuguan. If you don’t think about the blood, it’s a wonderful stew. Japanese food had raw fish for the longest time; nobody would touch it but now it’s everywhere. It’s about making people understand what it is.

How important is the way a dish looks on the plate to you?

In Chinese there’s this expression that translates to presentation, aromatic, and flavor. What it really means is that you begin with looking at it then you smell and finally you taste it. If all that is done well, it’s a complete dish.

Will you reveal what your most important kitchen utensil is?

The wok is the most important. You can do so many things with it. You can stir-fry, steam, braise meat, and you can make soup with it.

Originally published in F&B Report Vol. 13 Issue 1