More than 30 years ago, I started compiling vocabularies and writing dictionaries. I was 14 years old then, a second year high school student in Inopacan, Leyte. At that time, this quiet coastal town in the western part of Leyte had not seen the light and power of electricity yet. I used a lampara (kerosene lamp) at night to light my small room where I spent most of my time browsing through notes, old books, and a worn-out copy of Webster’s dictionary.

To sustain the light, I had to sell tangkong or swamp cabbage, a vine often used as fodder for pigs, so I could buy kerosene with the money. With an old and rusty bicycle, I peddled tangkong around town and delivered bundles of harvested vines to Aling Suling, an old lady who was then my suki in the town’s public market.

When it was time to harvest abaca in the mountain, I would join my mother to a remote barangay in the mountain to sell bread, dried fish, tinabal, inun-onang mangko, salt, and other commodities in small weight, just enough for us to carry around the village. I would join the local folks harvesting native coffee beans or in a group of manunuksi (abaca strips harvester) trying hard to flake lapnis (strips pulled from the bark of abaca) using the tuksi, a thin curve-bladed tool used in peeling strips of abaca fiber. The bundle of lapnis are later brought to the makina nga birahan sa lanot, a machine-operated hemp processor in which a skilled worker would insert pieces of lapnis and pull the hemp out with the help of a powerful rotating shaft. From the mountain, we had to walk our way to the lowland from morning until we reached home at night.

“My first job was at the provincial capitol of Leyte I served as the personal secretary of my uncle who was then elected provincial board member of Leyte. With my first salary, I bought my first English dictionary, a pocket Collins Gems English Dictionary,” shares Edgie Polistico.

I would use part of the money I earned to buy a ream of mimeographing paper, the brown and cheap kind of bond paper, for taking notes and writing my research. Some of the bond papers were folded into halves and bound to look like a thick book. That became my notebook in school.

Against all odds

Years went by very fast. When college came, my uncle sent me to Divine Word University in Tacloban City. It was in college that I seriously pursued my research on Visayan languages. Instead of wandering or hanging around with friends, I spent lots of my time in the Filipiniana section of the campus library. I became a bookworm, digging books and other publications for all sorts of information useful to my project until the library would close at night.

On weekends, after doing routine house chores and errands for the family who sent me to college, I would stay in the study room and continue my research using the big Oxford dictionaries of my uncle.

My first job was at the provincial capitol of Leyte. I served as the personal secretary of my uncle who was then elected provincial board member of Leyte. With my first salary, I bought my first English dictionary, a pocket Collins Gems English Dictionary.

“Sustaining the project took lots of time and money,” says Edgie Polistico. “It kept me awake past midnight and deprived me of a social life. But I would have regretted it more had I pulled out of the project.”

Because I could not afford then the cost of going back to school, I took the long and hard way of learning computer programming. It was in 2004 that I wrote and designed the first software application for the Edgie Polistico’s Cebuano-English Dictionary. When savings permitted me later to go back to college, I studied computer system programming and design at AMA Computer Learning Center in Makati City and Alabang.

Sustaining the project took lots of time and money. It kept me awake past midnight and deprived me of a social life. But I would have regretted it more had I pulled out of the project. I needed help, but it did not come when I needed it most. I appealed for support, even solicited financial assistance or any kind of help. No matter how small, help was badly needed to push and sustain the project. But it didn’t come. With all of what was left of my resources, I soldiered on and shared the updated dictionary software with others for free.

A few years later, I was still on my own, with hardly any help coming in. It was then that I decided to give up my research. I stopped updating the shared files. And my free downloadable app expired in 2012.

Bearing fruit

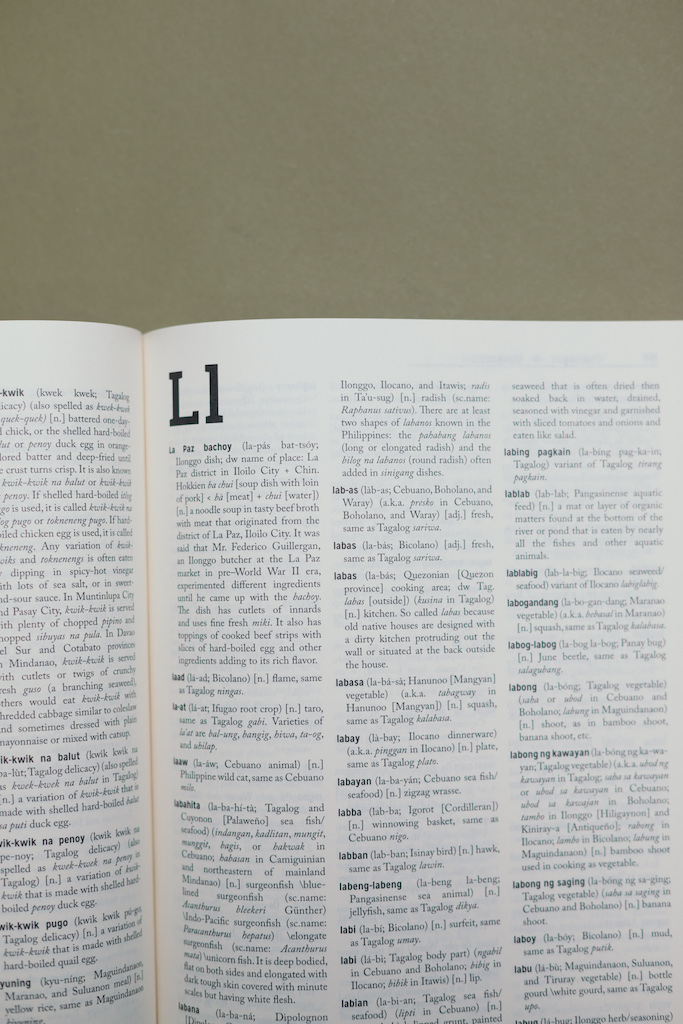

In 2008, I resurrected my files by producing Edgie Polistico’s Philippine Food Cooking and Dining Dictionary, a sample of which I posted online. The compilation mainly consisted of extracted food-related entries from my Cebuano-English dictionary, plus food names I learned from Waray and Boholano. The rest came from my visits to libraries and museums across the country and readings in various books, magazines, and other publications. My direct contact with locals and my actual experience with their food, culture, and languages also enabled my work to be more informative and invaluable.

I kept on updating and adding more entries to the dictionary in the years that followed—10 times more after the fourth update. In 2013, I submitted a script to Anvil Publishing and they were surprised with disbelief on how I made it. They showed it to food historian Felice Santa Maria, who then told the company that it was the kind of book she had been looking for since 1975. I was only a six-year-old boy then. Anvil and I signed the contract and the editorial job was completed in two years.

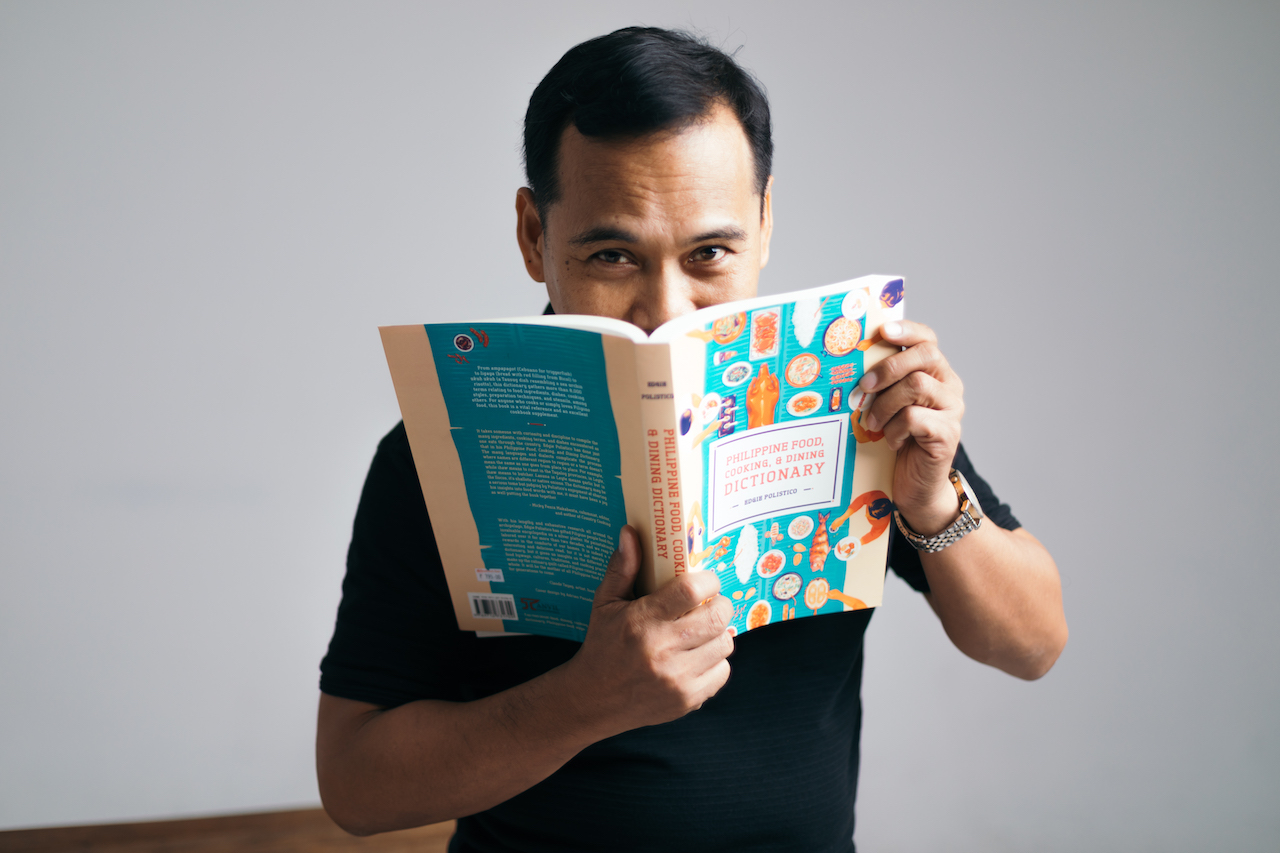

In 2016, my book, “The Philippine Food, Cooking, and Dining Dictionary,” finally saw print. Since then, it has won “Best in the World” in the Food Writing category by the Gourmand Awards as well as the “Best Book on Food” at the 36th National Book Awards.

Originally published in F&B Report Vol. 15 No. 1