Bohol has been a province broadly built by its tourist destinations: first, the famous natural landmarks of Chocolate Hills, Panglao’s beaches, and Loboc River; then by the new wave of adventures found north and inland; and finally, man-made attractions like adventure parks in Danao and Carmen that have claimed the attention of a younger demographic.

Yet ubi, arguably its most acclaimed food product, is characteristically connected with the land—a crop that is so essentially linked to the Boholano way of life, history, and identity.

“It was brought by the Spaniards,” says Larry Pamugas, OIC at the Office of the Provincial Agriculturist (OPA). “Dito na lang na-develop ’yung different varieties and then mixed with some local, endemic varieties. Though ubi first made its name in pre-Hispanic times when it became a “savior” during a famine, according to a The Bohol Chronicles report, it has retained its sacred status throughout centuries.

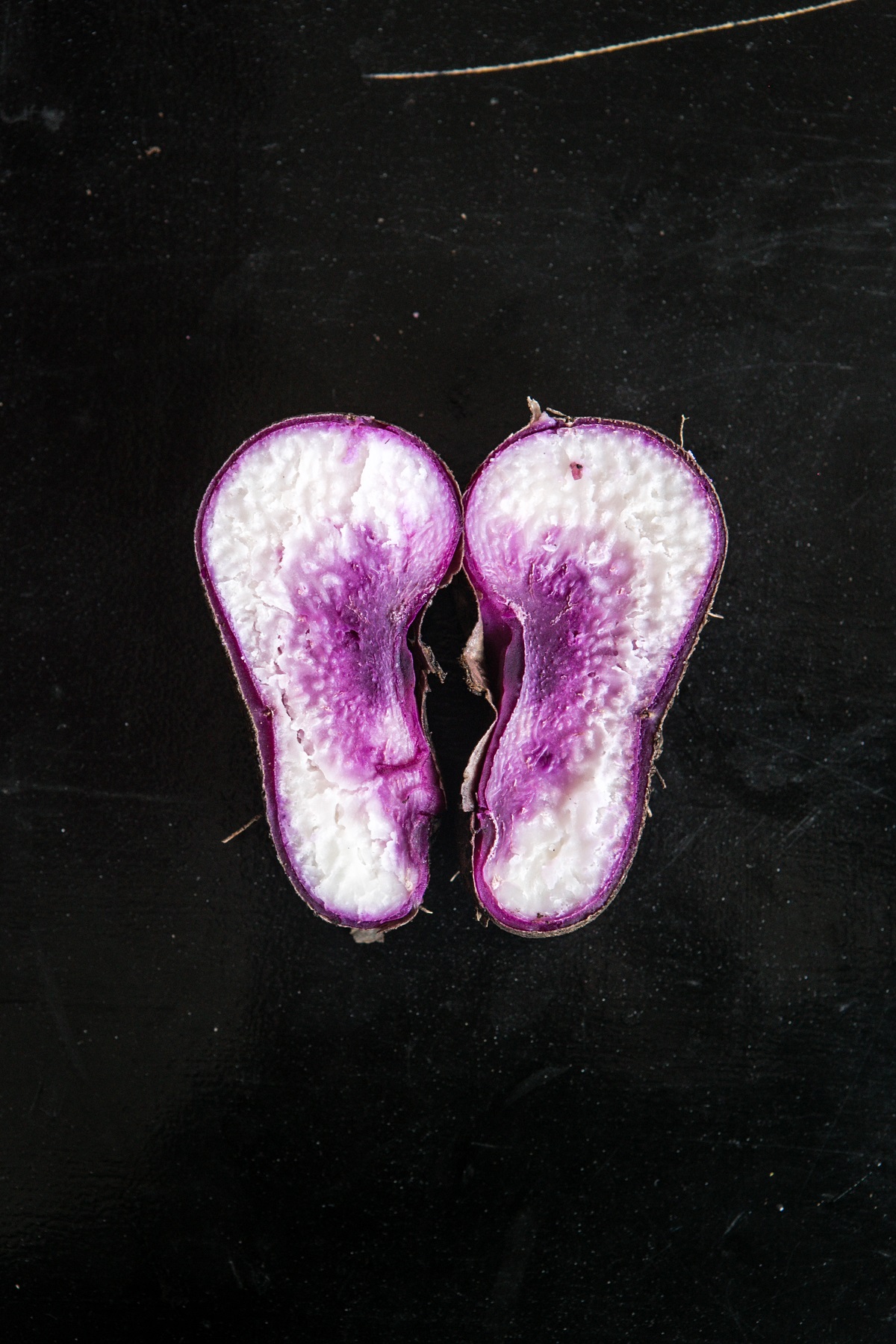

“Kasama na sa culture namin. Lalo na ’yung kinampay (an ubi variety),” says Pamugas, adding that not all municipalities have the capacity to grow the most famous variety owing to its color and aroma. Only specific coastal areas such as Albur, Baclayon, Corella, Cortes, Dauis, Panglao, Sikatuna, and Tagilaran are able to successfully produce the purple crop according to what people know today.

“Sa technical side, ang conclusion namin diyan is it might be because of the type of soil and climate in that area. Kasi ’yung kinampay ng Dauis itanim mo sa Ubay, ’yung aroma iba. The color is violet too, but the natural aroma is different.”

Though the effects of climate change have been unkind to Bohol—last year saw soaring temperatures and torrential downpours—the shared sense of pride in ubi and the products derived from it are often sublime enough to attract locals and tourists to spend on the priority crop.

Flourishing business

Scattered across Tagbilaran City are restaurants and shops that are rich in ubi history. And many of these have thrived and evolved into a crucial stop on the tourist trail. At the Bohol House of Ube, one of the pioneer brands from the Labad family, you can purchase jams and pastillas while the Bohol Bee Farm, makes a powerful connection with its ubi-flavored homemade ice cream.

Today, new brands like Too Nice to Slice Cake Gallery are characterizing fixtures in the scene. Started by the Lapura family in May 2016 as a venue for Lily Lapura Quina’s desire to create cakes in all shapes and sizes, the small family business has since transformed itself into a corporation this year after public demand helped spur the business into new directions.

The global enthusiasm for ubi seems to be a cause for celebration, but a practical look at the grassroots level explains the potential dearth in the region.

“I thought about [putting up a business] when I used to work in a call center in Cebu. As a sideline, I used to bake cakes and sell them,” she says. “Eventually I just wanted to stop working and start my own business. My brother Williamson said he can be in charge of the meals. Just a week after, we started serving meals aside from cakes because people asked for it.”

Their hybrid sensibility where one side of the business serves cakes and the other serves savory boodle-style meals is playful yet classic in the way they acquire new markets and integrate their feedback into the menu. Right now, Too Nice to Slice Cake Gallery regularly sells up to 30 500-gram ubi jam jars daily, but during peak season, Williamson says, sales can easily double. While their influence has slowly enabled them to be a considerable household name in Bohol, it’s their investment in ubi that has given them the springboard take on more established brands.

And with a heritage kinampay recipe from their mother Alegria spearheading this diversification, the new generation leadership of Lily and Williamson couldn’t have come at a better time, when Bohol is eagerly awaiting the opening of the international airport. Still, their direction remains true to their roots.

“What makes our jam different,” says Lily, “is that others use kamote because it’s cheaper and more readily available. Ubi is harvested only once a year and towards the end of the year it’s difficult to find it. But for us, we just use pure ubi.”

In danger

While some businesses appear to be booming, the OPA tells a different story. As the demand for ubi products increases and provides an economic boost, the farmers serving this surge suggest an alternate reality. Once typified by growing numbers, ubi farming now faces a lack of successors, climate change, and a general disinterest in agriculture.

“Before, ang ubi kahit saan mo ilagay tumutubo pero ngayon tumutubo man pero hindi umaabot sa maturity,” reveals Pamugas. “Threatened kasi ang ubi ngayon due to climate change. Lalo wala nang farmers na nagtatanim. This is one of the threatening factors for Philippine agriculture: aging farmers and fisherfolk, no government programs, ’yung mga bata natin nasa IT na lahat, kahit graduates ng agriculture, basta hindi na babalik sa farm.”

As the demand for ubi products increases and provides an economic boost, the farmers serving this surge suggest an alternate reality. Once typified by growing numbers, ubi farming now faces a lack of successors, climate change, and a general disinterest in agriculture.

Statistics from the OPA also indicate that area allotted for planting and harvesting ubi has steadily declined—from 2,720 hectares in 1990 down to 854 hectares in 2016. It’s an alarming plummet that has called for desperate measures, which forced them to buffer or color and perfume alternative root crops like lima-lima (a cross between ubi and sweet potato) to pass for ubi.

Last year, some crops were also delayed because of heat, and then in October, there was too much rain, which caused a delay in maturity. Another notable finding involves taking into account how Boholanos view the product.

The context hasn’t shifted from a so-called “backyard thinking” approach, which Pamugas says accounts for 500 to 600 hills as opposed to the commercial scale of some companies that use plains up to two hectares wide, to a more enterprising method.

“Hindi pa talaga naisip ng mga Boholano na ’yung ubi is a source of income. Maliban lang ’yung ibang grupo na commercialized ang approach. Then ’yung mga members ng Bohol Ubi Growers Association talagang commercial scale na.”

Much more than an ambitious project, OPA’s enthusiasm to address issues, modernize farming technology, and expand their reach remains a priority. The OPA’s architecture is designed to match suppliers and buyers to avoid oversupply, oversee crops and fisheries in the province, and conduct research to sustain agriculture. Vegetable diversification is another comprehensive strategy the region is looking at. Bohol is actually second when it comes to seaweed production, next only to Jolo; coconut and rice are big industries, too.

“We’re also happy that we have a research station (Bohol Experiment Station) that also lists ubi as a priority crop in their research,” says Pamugas. Tissue cultures, for instance, are done for the source of planting materials. “Kasi ’yung ubi kapag hindi mo natanim mga two to three months, mag-de-deteriorate ’yung quality. Tsaka madaming sakit. ’Yun ’yung sino-solve ng tissue culture natin.” Although it’s not to say that ubi is an easy crop to handle, because as Pamugas says, it takes “three generations or three years before farmers will be able to use it as planting materials.”

And despite the Ubi Festival’s enduring efforts, which was launched by the local government 18 years ago, to acknowledge ubi growers, gather investors and stakeholders, and morph into a trade fair and consumer show, much more needs to be done beyond just the short-term outlook.

“Ubi is just a dream,” says Pamugas. “Fifteen years to go and wala na.” Indeed, on the surface, the global enthusiasm for ubi seems to be a cause for celebration, but a practical look at the grassroots level explains the potential dearth in the region. It’s a marked shift from what consumers believe: that the trending purple yam is directly tied to the proliferation of growers. Before long, this purple patch could soon turn black.

Originally published in F&B Report Vol. 15 No. 3

Sino po pwede makontact regarding ube deseases? Salamat.

Sino po pwede ma contact. Interesado po akong bumili ng mga ube mula 5 tons pataas po. Salamat po . Ito po ang number ko 09273146061